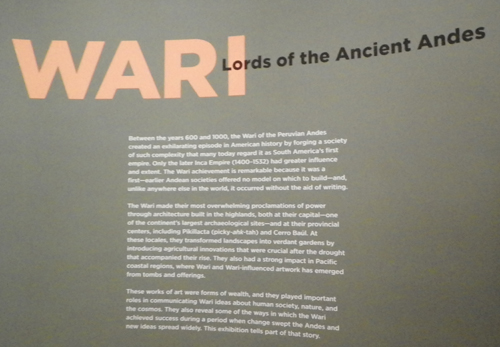

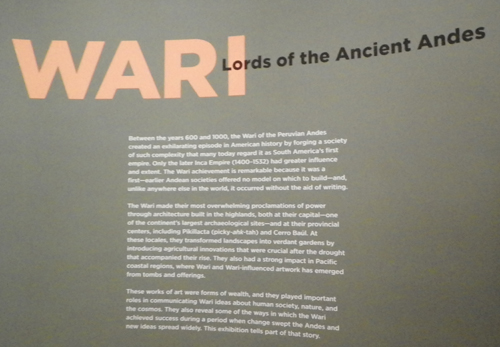

The Cleveland Museum of Art is home to a fabulous exhibit, Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes. It is the first exhibit of its kind in all of North America. When it leaves Cleveland it is travelling to Fort Lauderdale Florida and Fort Worth Texas.

See more from the Cleveland Museum of Art exhibit Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes.

The Wari are generally regarded as the first of Peru's empire tribes. Their time in Peru lasted about 400 years, between the years 600 and 1000. This was long before the better known Inca Tribe.

Their society was complex, and could even boast an amazing aqueduct system, certainly one that could rival that of Rome.

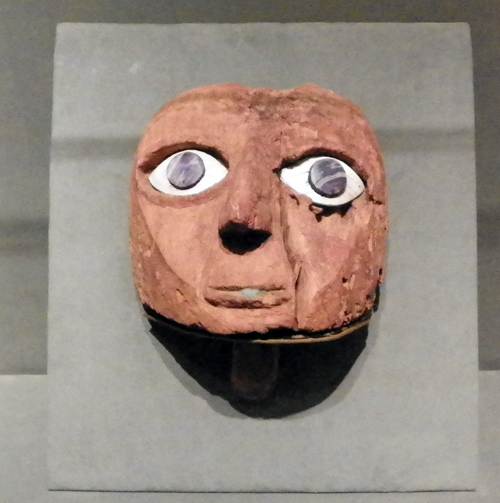

The exhibit houses 150 artifacts showcasing all of the Wari media of expression. There are beautiful textiles including hand weaving, tie-dying and embroidery. There are ceramics, metals including gold and silver and sculptures.

There appears to be no written language for the Wari, but there art and relics none-the-less tell a story. They seemed to have communicated through color and texture, if not handwritten words.

The following excerpts are taken from The Cleveland Museum of Art Study Guide and offer some insight into these fascinating people.

Early inhabitants of the Andes faced many challenges in agricultural production. The desert Pacific coast experiences very little rainfall and the extreme altitude of the highlands results in cold, harsh conditions that limit the variety of crops that can be cultivated.

However, by planting crops at different altitudes, and by building settlements in fertile coastal river valleys, the Wari were able to grow a variety of crops, including potatoes, maize, and cotton. In addition, raising domesticated llamas and alpacas provided the Wari with meat and fiber for making textiles. The harnessing of these resources was an important achievement in ancient times and many of these resources

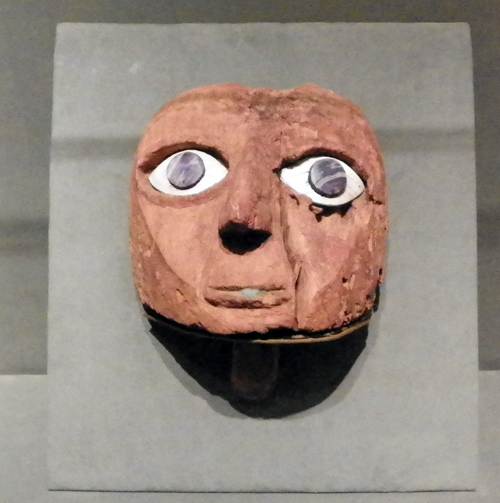

held important roles in religious rituals, which often dealt with themes of fertility and abundance. Many ceremonial ceramic vessels feature representations of these resources. When examining Wari art, look for depictions of maize plants and llamas-important resources that continue to serve as fundamentals of Andean culture today.

During the Wari period certain imagery spread very widely, especially a front-facing staff deity and winged profile attendants. These images are thought to represent the most important divine personages

of the Wari religion, recognized as supernatural or divine due to characteristics such as vertically divided eyes, fangs, and/or wings. These supernatural figures appear frequently on finely crafted tapestry-woven tunics worn by elite members of the Wari state. Were the people that wore these tunics rulers or priests? Although we tend to consider religion and politics as distinct realms of a society, it is likely that they overlapped for the Wari. Many of their objects and images appear to communicate a unity between political power and religious practice, such as ceremonial pottery in the form of a human, perhaps an administrator of the Wari Empire, who is dressed in a tunic bearing images of divine figures. Furthermore, many representations of humans are depicted holding staffs, a powerful symbol of both earthly and divine authority in the Andes. Without knowing the details of Wari religious beliefs,

we can nevertheless deduce from the objects they made that deities and religion played an important role in the ability of the Wari society to rise to power, build great urban centers, and expand far beyond the region surrounding their capital city.

Feasts and Offerings. Gift exchange is, and has been, practiced all over the world, at all levels of civilization. It is a powerful social custom that establishes systems of reciprocity and maintains bonds between people. One very important way that the Wari practiced gift-giving was through feasting. By

hosting lavish feasts for the leaders of other regions, the Wari may have gained their cooperation along with access to desired resources, including much-needed labor to produce more crops and build more structures, allowing the Wari Empire to grow ever more powerful. Following a similar logic, members of the Wari elite would make offerings of various kinds, including human sacrifices, to supernatural forces in an effort to receive favorable conditions for abundant harvests and prosperity.

Finely crafted vessels painted with rich colors, some even detailed with three-dimensionally modeled faces, are examples of the type of pottery that would have been used for feasts and offerings. The Wari had a tradition of smashing these fines wares and burying their remains, but the reasons behind this practice are unclear.

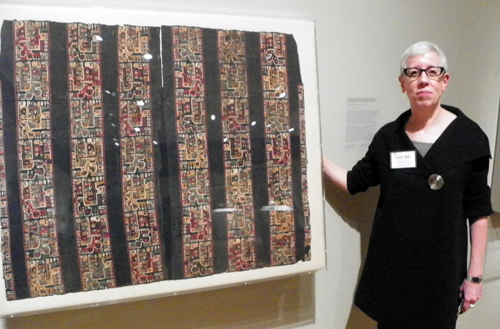

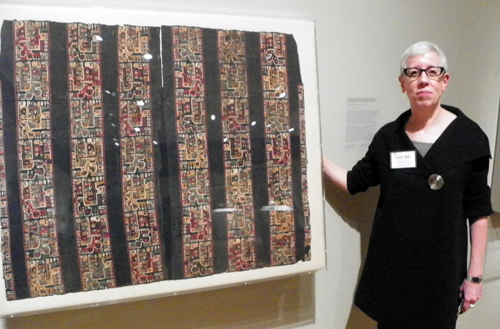

It is true that the Wari, like other ancient Andean civilizations, never developed an alphabet or any form of written script. They did, however, have a system of recording information on a string device called the khipu. Unlike an alphabet that is designed to record words, khipus seem to have been designed for recording numerical information of many kinds. Such a device was likely important as the Wari Empire expanded and more and more societies were brought under its control and were expected to pay tribute to their subjugators. In fact, many aspects of Wari material culture indicate that the Wari were an analytic society that valued highly organized systems of information. This can be seen in the gridded plans of urban sites like Pikillacta, and also in their tapestry-woven and tie-dyed tunics, which follow complex systems of symmetry and color patterning. While Wari art is celebrated for being beautifully crafted, little of it seems to be merely decorative.

Khipus and textile patterns in particular can provide students with case studies to practice abstract quantitative and spatial reasoning. The process of decontextualizing a khipu or a visual pattern on a tunic will challenge students to analyze the mathematical structure beneath the object, and recognize the logic behind Wari design. Students will discover how they can access an ancient civilization through the language of mathematics.Abstraction and Distortion in Tapestry Tunics. In the Andes, weaving was such a fundamental skill that it may have shaped the way Andeans approached problem solving. The Wari not only used the medium of textiles to produce images, but they also used the process of weaving to develop new ways of designing images. On tapestry tunics, figures that otherwise appear easily visible on pottery-usually winged figures in profile carrying staffs-are geometrically stylized in a way that mimics the rigid structure inherent in loom weaving. Yet it is important to realize that the images were not limited by the

weaving technique itself; Wari weavers used the same tapestry technique that was popular in sixteenth-century Europe for creating naturalistic scenes of people and landscapes. Rather, the abstraction of the figure to geometric forms is better understood as an aesthetic choice on the part of the weaver, or of Wari society in general. This highly analytical method of manipulating the image has been compared to Cubism, a system of abstraction developed by Picasso and Braque in Paris in the early twentieth century.

Like a Cubist portrait, Wari figures become difficult to identify in what appears to be a purely abstract composition of geometric shapes. One especially innovative technique of abstracting the image that goes beyond the initial geometricization of the figure is one in which the motif is expanded and contracted until the original image becomes severely distorted, sometimes beyond recognition. The question of why the Wari preferred such abstract and distorted imagery on textiles and tunics is one that continues to challenge art historians.

The Wari exhibit continues through January 6, 2013 and is not to be missed.

Curator Sue Bergh

Sue Bergh, Curator of Pre-Columbian and Native American Art, is curator of this exhibit. Her vast knowledge, appreciation and respect for the project is conspicuous in the details and presentation of the exhibit. Back to Top

Back to Cleveland Peruvians

Back to Cleveland Hispanics

|